Cat-Loving Haruki Murakami and the Abundance of Movie Adaptations

Cat-Loving Haruki Murakami and the Abundance of Movie Adaptations

Disclaimer: Information concerning sources and images used can be found in the concluding section of the article. The Author's Endnote section enumerates movie titles that are accessible in the West via either streaming platforms or physical media. To avoid formatting issues, there are no captions under screenshots of movies in the main body of the text. Should you wish to know the name of a film on the basis of a picture, please click on it and it will send you to the appropriate site. This article can be viewed in dark mode.

Western fans often call him the “drifting director” or the “vagabond of time”. Some overzealous academic researchers even go so far as to say that he is a hippie version of Franz Kafka who overdosed on LSD. Truth be told, Nobuhiko Obayashi embodies and eludes all of these descriptions at the same time. Contrary to common misconceptions, he was not just an expert at trippy horror flicks. He was a versatile director and a true visionary in his own right.

I remember having a conversation online back in April 2020 about how cool and indestructible Obayashi really was. This man directed 43 feature movies, 10 short films, and over 2000 commercials in the course of his 50-year-long career. In spite of being diagnosed with stage IV terminal cancer, and with a prospect of a few months left to live, Obayashi had not given up and completed his passion project known as Hanagatami (2017) and had the strength to make another movie in 2019 called Labyrinth of Cinema. I was hoping that this legend would grace us with yet another motion picture, but unfortunately, shortly after my conversation, I heard the saddening news that Nobuhiko Obayashi passed away at the age of 82. It was at that moment that I realised just how little I have seen of Obayashi’s movies. This gave me the motivation to explore his vast and rich filmography. To me, discovering the works of the late Nobuhiko Obayashi felt like transcending the multi-layered plain separating our reality from the surreal dreamscape. Dear MDL-ers, without further ado, I am providing you with a special guide to Nobuhiko Obayashi.

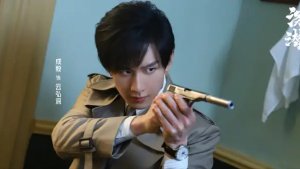

Personal Details |

Nobuhiko Obayashi with his daughter Chigumi (circa 2015). |

|

Early Life and Education |

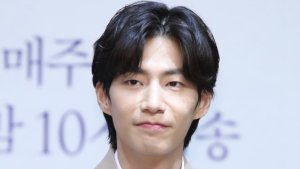

Nobuhiko Obayashi and his wife Kyoko (circa 1968).

Nobuhiko Obayashi and his wife Kyoko (circa 1968).

Nobuhiko Obayashi was born on the 9th of January, 1938 in the city of Onomichi, which faces the Seto Inland Sea and is located in the Hiroshima Prefecture. His father was a medical doctor who was drafted into the army, whereas his mother specialised in tea ceremonies. Young Nobuhiko was part of that peculiar generation of Japanese people who were too young to fully comprehend the atrocities of war, yet old enough to have clear, haunting memories of militarist propaganda: “For instance, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the boys were chanting, ‘Japan won! The enemy is defeated! We beat Roosevelt and Churchill! Japanese might is great!’ With lanterns in our hands, we were on a spree. But it only took four years for things to drastically change,” remembers Obayashi (source). Needless to say, the childhood experiences in Onomichi would prove to have a major impact on his manner of cinematic storytelling (source: Jacoby and Richie).

Under the care of his maternal grandparents, Nobuhiko was encouraged to develop his interests in filmmaking, animation, painting as well as music. Already at the age of six, he started making short 8mm films. Nevertheless, Obayashi’s father, who gave him his first-ever camera, persuaded him to enrol at a medical university. Nobuhiko did just that out of respect for his father; however, he quickly dropped out. In 1956, he became a student in the liberal arts division at Seijo University (source). In the course of his studies, he directed his very experimental short film called The Girl in the Picture (1958), a story about a painter who loses his lover literally as well as artistically because her image disappears from his drawing. Interestingly, the heroine of Obayashi’s debut film was Kyoko Obayashi, the director’s wife who later became the producer of his movies.

Short Films Director & Commercial Man |

After his university endeavours, Obayashi became interested in the avant-garde movement as well as experimental filmmaking. He formed together with Takahiko Iimura, Yoichi Takabayashi, and film historian Donald Richie an independent filmmaking group called Japan Film Andepandan (source). Having been influenced by the French New Wave and Jean-Luc Godard, Obayashi developed his own idiosyncratic style of filmmaking which consisted of various ingenious strategies, such as changing the frame rate of footage (slowing down or speeding up the film), utilising stop motion, crosscutting live-action footage with hand-drawn animation, shifting picture format between 4:3 and 16:9, blending coloured scenes with black-and-white ones, and making composite shots with the usage of blue screen and matte paintings. The editing itself cannot go unnoticed because Obayashi preferred a very rapid method of cutting a film together, almost as if the images preceded the actual narrative (source), which gave the peculiar, chaotic, and nearly unnerving quality to his pictures. In addition, apart from original music scores made by film composers, he also preferred to include classical music (Liszt, Brahms, Puccini to name but a few). This stemmed from his background as a pianist (source).

After his university endeavours, Obayashi became interested in the avant-garde movement as well as experimental filmmaking. He formed together with Takahiko Iimura, Yoichi Takabayashi, and film historian Donald Richie an independent filmmaking group called Japan Film Andepandan (source). Having been influenced by the French New Wave and Jean-Luc Godard, Obayashi developed his own idiosyncratic style of filmmaking which consisted of various ingenious strategies, such as changing the frame rate of footage (slowing down or speeding up the film), utilising stop motion, crosscutting live-action footage with hand-drawn animation, shifting picture format between 4:3 and 16:9, blending coloured scenes with black-and-white ones, and making composite shots with the usage of blue screen and matte paintings. The editing itself cannot go unnoticed because Obayashi preferred a very rapid method of cutting a film together, almost as if the images preceded the actual narrative (source), which gave the peculiar, chaotic, and nearly unnerving quality to his pictures. In addition, apart from original music scores made by film composers, he also preferred to include classical music (Liszt, Brahms, Puccini to name but a few). This stemmed from his background as a pianist (source).

Consequently, Obayashi went on to make more short films in the 1960s, like Dandanko (1959), Thursday (1960), Remembrance (1963), and The Man Who Was Eaten (1964). The last short in particular deserves a mention. It is a 20-minute silent vignette that explores the relationship between eating and material consumerism. In his subsequent projects, you can spot the aforementioned visual tropes and special effects which would later become part and parcel of Obayashi's distinct movie style. For example, Emotion is also worth noting because it functions as a stylistic prelude to House (1977). Obayashi himself stated that the short is a “monument to youth” and a love letter to Roger Vadim’s Blood and Roses (1960) (source). It is basically a multicoloured, multi-narrational (in English and in Japanese), hallucinatory love story in which a girl falls for a vampire.

|  |

In one of the last shorts, Foreign Correspondent - The Case of a Filmmaker (1968), Obayashi presents a fictionalised documentary about himself, his family and friends, told from the perspective of a European art designer. We get a lot of behind-the-scenes insight into Obayashi being on a set and directing. It is a small, beautiful endeavour that serves as a perfect example of Obayashi's unconventional play with cinematic metanarrative style. In 1968, he also made Confession (1968), which similarly to Emotion provided a kaleidoscopic spectacle of colourful vignettes focusing on the youth having fun in the town of Onomichi.

Obayashi’s short productions were not officially picked for mainstream distribution; however, they were making rounds at universities and foreign film festivals as samples of underground filmmaking. During a screening event in Shinjuku, Obayashi and his fellow artists were approached by a representative of Dentsu, a large advertising company. The agent offered them an opportunity to utilise their experimental skills while making TV ads. Only Obayashi accepted the offer, tempted by a chance to work with professional filmmaking equipment and bigger budgets.

As a result, Nobuhiko honed his craft on the backlot of Toho Studios by shooting advertisements with Hollywood legends and celebrities, such as Sophia Loren, Catherine Deneuve, Charles Bronson, Kirk Douglas, and Ringo Starr. These were snappy and innovative clips from the Bubble Era of Japan which promoted rampant product materialism and Japanese infatuation with foreign movie stars. Personally, I can’t get out of my head the Bronson ad in which the actor’s sojourn at a hotel is crosscut with Wild West imagery just to crank up the aspect of manliness.

House (1977) |

I remember that a few years ago when I delivered a lecture on Japanese Cinema at a local high school in my hometown, I showed students clips of House taken out of context and asked them which popular director made this movie. Many names were dropped in the classroom, including David Lynch, Tim Burton, Peter Jackson, and even Koji Shiraishi(!), but nobody mentioned Nobuhiko Obayashi.

This wonderfully crazy parody of the horror genre appears to be a creative juggernaut that overshadows the rest of Obayashi’s filmmaking career. Everybody talks about it in the West but no mainstream critic dares to acknowledge the fact that Obayashi was not a horror-obsessed director; that he was not afraid to challenge himself in a variety of other genres.

Eventually, the director’s commercial input got the attention of Toho executives. The late 1970s were a dire time for Japanese Cinema because it was forced to compete with the cheap and easily accessible domain of Television. Toho was losing money on straightforward yakuza flicks or even Godzilla spectacles. The only pictures that were selling belonged to pinku eiga trend. Having noted the spectacular success of Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975), the studio executives hoped to get a piece of the pie by making their own brutal horror movie set in a similar tone. They turned to Obayashi who was not really keen on making a Jaws rip-off. In one of the interviews, he stated the following: “At that level, a hit movie about shark attacks leads to one about bear attacks. That’s the best they can do” (source).

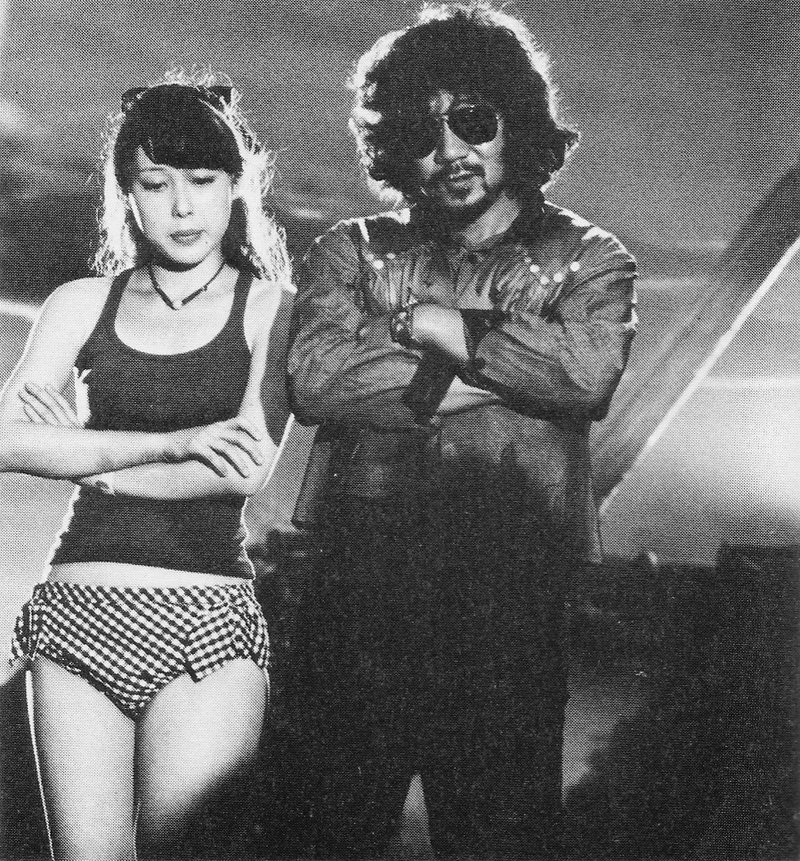

|  |

Obayashi wanted his feature-length debut to be original and unique, scary and funny at the same time. To ensure the ingenuity of House, he turned for ideas to his then 11-year-old daughter Chigumi, who described all the things which she found terrifying, but which were mundane to a boring adult. Obayashi wanted to capture that childish, unlimited, phantasmagorical imagination and translate it into a movie language. He even managed to slip in an anti-war reference as well. The end result is a story about a haunted house that devours innocent girls.

Obayashi’s enthusiasts can speak in large quantities about House, so let me just conclude this section by saying that I find House to be a deeply romantic motion picture, yet disturbingly chilling at its core. Some say it is a postmodern spectacle of absurdist meaninglessness, whereas others call it “bubble-gum meets gothic aesthetic” (source). In my opinion, this is a tragic story about women losing their childish innocence and facing brutal reality because men failed to become knights in shining armour. Oshare (Kimiko Ikegami) repeats the fate of her aunt by transforming into a demonic bride and scorching her would-be stepmom into oblivion. I encourage you to watch the film on a sunny evening to fully immerse yourselves in the dreamlike reality of House.

Post-House (1977-1979) |

Needless to say, House became a massive commercial success in Japan. It was originally run at cinemas as a B-movie feature accompanying a different motion picture (source), but its immediate popularity led to stand-alone screenings later on. Obayashi, a guy doing quirky commercials, became a studio-based director.

Immediately after House, he made for Toho The Visitor in the Eye (1977), an adaptation of Osamu Tezuka's famous Black Jack manga. This is a movie in which he showed for the first time that he could put his personal spin even on an adapted material. That is to say, The Visitor in the Eye is not a crime drama centering on Black Jack, but a love story outrageously inspired by French and Italian Cinema. Nobuhiko demonstrates his craft and love for movies in the story filled with heartbreakingly brilliant cinematography and enchanting music score. Obayashi certainly knows how to build a mood with sound and image, as we see a romance in motion between a girl and a mysterious man whose phantom appears in her eye.

San Francisco is renowned as the shooting location for such movie franchises as Star Trek, Bond, and Godzilla. It comes as no surprise that Obayashi went there and shot his movie there too. Take Me Away! (1978) remains the only movie made by Nobuhiko in America. It is by and large a conventional romance film with touching performances of the main leads, Tomokazu Miura and Momoe Yamaguchi. This movie makes me wonder what Love Story (1970) or The Way We Were (1973) would have looked like had Obayashi directed these pictures.

In The Adventures of Kosuke Kindaichi (1979), Nobuhiko Obayashi presents us with a popular character of a Japanese detective, created in 1926 by a mystery novelist Seishi Yokomizo; nevertheless, the movie itself is not by any means a standard crime flick. On the contrary, Obayashi crafted a meta-story way before Being John Malkovich (1999) or Adaptation (2002). Kosuke Kindaichi (Ikko Furuya) is very much aware of the numerous novels and movies about him, and of that, he is a man out of context, unfit for the City Pop vibes of Japan of the 1970s. Consequently, he is locked within clichéd tropes and plot twists (corpses, fake suspects, dramatic reveal of the culprit), forced to do his detective work time and time again with the aid of Inspector Todoroki (Kunie Tanaka). Yet, Obayashi puts an absurdist spin on the whole thing, sprinkling The Adventures of Kosuke Kindaichi with The Naked Gun-type of humour and numerous references to popular culture (Superman, Dracula, Dancing in the Rain, Saturday Night Fever). The director even playfully throws shade at his commercial background and previous works like House and The Visitor in the Eye. The best way to describe the film is to call it cheerful insanity. Easily one of the best scenes is the one in which Kosuke is forced to watch a film in which the fictionalised version of himself is played by... Toshiro Mifune.

The 1980s |

The Adventures of Kosuke Kindaichi is often regarded as the culminating point of Obayashi’s first phase as a filmmaker. The decade of the 1980s can be best described as the “Golden Age” of Obayashi because he created lots of memorable youth-centred movies throughout that period.

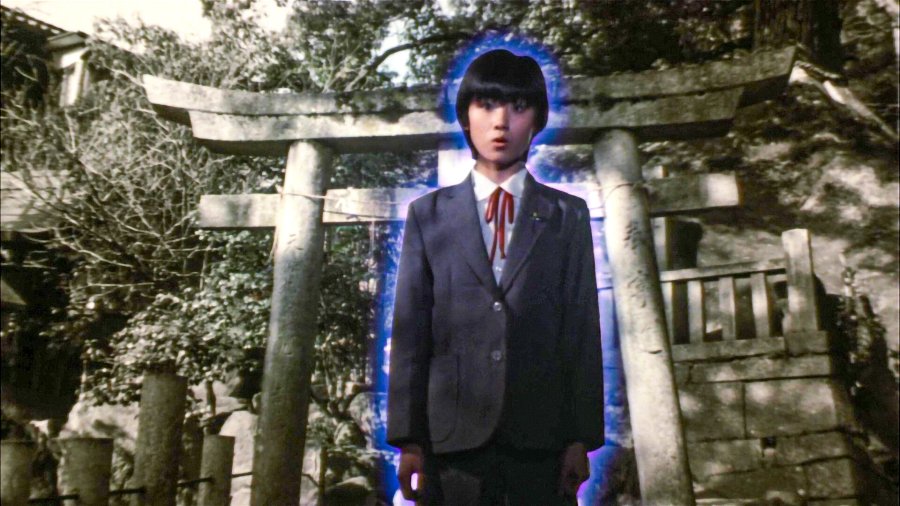

School in the Crosshairs (1981) is a fine example of Obayashi’s auteur manner of filmmaking. It is not a film just about school and it is not just about teenage love, it is about students with supernatural abilities fighting against each other. Basically, aliens from Venus take control over the high school by setting up a para-militaristic group that terrorizes everybody. The only hope to restore order is a schoolgirl (Hiroko Yakushimaru) who discovers that her psychic powers influence the outcome of events. Perhaps Obayashi wanted to wove his anti-militarist sentiments into the story, or he just wanted to go crazy. School in the Crosshairs is highly imaginative and universal with its symbolism and, in my opinion, evokes the popular X-Men franchise. Top-notch special effects cannot go unnoticed, such as surrealist matte paintings, colourful composite shots as well as rotoscopic effects during the action scenes.

Whereas School in the Crosshairs was about a heroine who discovers magical powers and eventually rejects them, Obayashi’s next film is about a supernatural event that is beyond the protagonists’ control. Exchange Students (a.k.a. I Are You, You Am Me) (1982) is a thoughtful and funny take on the popular motif of body swapping. Obayashi shot the film in his hometown Onomichi, which already served as a location for Yasujiro Ozu, Akira Kurosawa, and Kaneto Shindo. In addition. It was also the first time when the director worked with actor Toshinori Omi, who went on to play leading roles in many subsequent Obayashi’s films. Exchange Students is a very sweet and light-hearted movie that enjoys great popularity in Japan. The performance of Satomi Kobayashi is amazing and we also get to see the wonderful Kirin Kiki in a supporting role. I am pretty sure that the falling-down-the-stairs scene inspired a similar sequence in Tengoku to Jigoku: Psychona Futari drama.

Also in 1982, Obayashi directed a made-for-TV horror for the Tuesday Night Suspense Theatre slot. Cute Devil (a.k.a. Lovely Devils) is basically Nobuhiko's take on The Omen type of story in which a little girl turns out to be a ruthless murderer. It is simple and at times conventional (evil child, crazy mother, isolated house on a hill), yet incredibly effective. The movie shows that Obayashi was resourceful even with a small budget at hand. On the whole, Cute Devil manages to strike the chord of Freudian insanity before Park Chan Wook's The Handmaiden (2016).

|  |

The Little Girl Who Conquered Time (1983) is yet another Obayashi movie based on external source material. It also features an idol in the leading role, an aspect that would go on to become prominent in many of Obayashi's movies of the 1980s. It seemed as if this was his deal with producer Haruki Kadokawa whose company was really engaged in promoting idols on the big screen. “When I was still young, my job was to raise newcomers, people I had met for the first time, into stars,” the director recalled (source). The movie itself is often compared by critics to Groundhog Day (1993), but I think this parallel does Obayashi a disservice. The movie is a clever spin on the time travel premise as the main heroine (Tomoyo Harada) bends time and space, jumping in-between various points of her life in search of teenage love. If anything, it feels like The Wizard of Oz (1939) (and Obayashi included an Easter egg referring to that film). It is all about youth, childhood memories, and sentimentality. The third act is just amazing to look at, and it is quite impressive how beautiful Obayashi made it just with analogue trick photography.

Interestingly, Kenya Boy (1984) remains Nobuhiko's only anime feature project. Anime enthusiasts on the internet point to many technical peculiarities of the film, concluding that the animation was not fully finished. Well, the drama behind the scenes remains unconfirmed to date, but personally, I love Obayashi's approach to animation. Some of the shots transitioning between coloured sequences and sketched scenes back and forth are really beautiful. Nevertheless, the screenplay, based on a manga from the 1950s, is a missed opportunity. It desperately tries to repeat the vibes of Tarzan but comes off as stereotypical and clichéd (animal cruelty, villainous natives, hot damsel in distress without personality). Not to mention that the third act is completely bonkers. There is a high-tech lab in the African jungle where Nazis are developing the atomic bomb... Well, the director certainly managed to emphasise his anti-war sentiment, but the film, on the whole, is unwatchable. It is especially unfit for children.

The Island Closest to Heaven (1984) is another project adapted from a novel. This time, there is no usual Obayashi's visual extravaganza. The storyline very much relies on the real locations of a beautiful, tropical island. This is a movie about love, melancholy, and the Japanese immigrant experience within the French territory of New Caledonia. In terms of aesthetics, it feels like a classic black-and-white Hollywood picture with regard to tranquillity and nuanced mannerisms of the performers, yet there is still room for vibrant colour, especially the ever-important for Obayashi symbolism of the sunset.

|  |

Obayashi returned to Onomichi again in Lonely Heart (1985). The movie presents the viewers with a typical boy-loves-girl structure, but all of a sudden, the narrative takes a U-turn when an additional character is introduced. That is to say, the protagonist (Toshinori Omi) encounters a 16-year-old phantom-like alter ego of his own mother (Yasuko Tomita)! Rest assured, Lonely Heart is neither psychoanalytical nor NSFW. In a positive and nostalgic way, Obayashi points out that our parents were also young in the past and they too had love dilemmas. Sometimes it is best to cherish good memories and embrace the process of growing up.

The year 1985 also saw the release of yet another absolutely amazing Obayashi movie called Four Sisters. As the title suggests, the story centres around four heroines who accidentally discover that they are not related by blood. Every frame of the film is so breathtakingly beautiful. I felt literally bombarded with aesthetics and the plight of the sisters brought me to tears. In my opinion, Four Sisters is a MUST SEE if you are into family dramas. As I have stated in my initial reaction after watching the film. it broke my heart, glued it back, then broke it again only to glue it together once more. Make sure to prepare a bag of tissues for this one.

In His Motorbike, Her Island (1986), Obayashi focused on a love triangle between a boy (Riki Takeuchi), a girl (Kiwako Harada), and a motorcycle. It is definitely something more than a standard bosozoku flick. Although the film is less wacky than Sogo Ishii’s Crazy Thunder Road (1980), it functions very much like its companion piece. In fact, I believe it should have been called "Crazy Thunder Road 2: Love Warrior". The unlikely romance is explored through monochromatic shots as well as vividly colourful ones, and the ending just grabs you by the heart.

|  |

The same year, Nobuhiko also churned out his classic anti-war drama, and arguably most personal film, called Bound for the Fields, the Mountains, and the Seacoast. This motion picture is the true progenitor of Hanagatami (2017) in terms of its thoughtful exploration of Japanese society during wartime, brutal critique of the military, and idealistic praise of the youth. It has to be noted that the movie was released in two versions: one being black and white, and the other entirely colourised. Personally, I recommend that you check out the colour edition first, and then turn on the B&W edition just for the sublime visuals.

After tackling a difficult subject matter, Obayashi turned to lighter material. The Drifting Classroom (1987) is the only Nobuhiko Obayashi movie that I truly dislike. It is all over the place. Even though it was based on a manga, the director took great liberties with the source material. Of course, you can spot his auteur style in each and every scene, but it is not enough to elevate this picture to a status of an entertaining one. It seems as if Obayashi wanted to make a child adventure flick like Spielberg’s E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982) or Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). Nevertheless, the end result is the following: The Goonies on the planet Arrakis; however, the protagonists behave in a clumsy, erratic, utterly embarrassing way, and the dialogues are just atrocious at times. Still, the movie enjoys a cult following among Obayashi’s fans mainly due to the visuals and the fact that English cast members are open about discussing it nowadays (source).

|  |

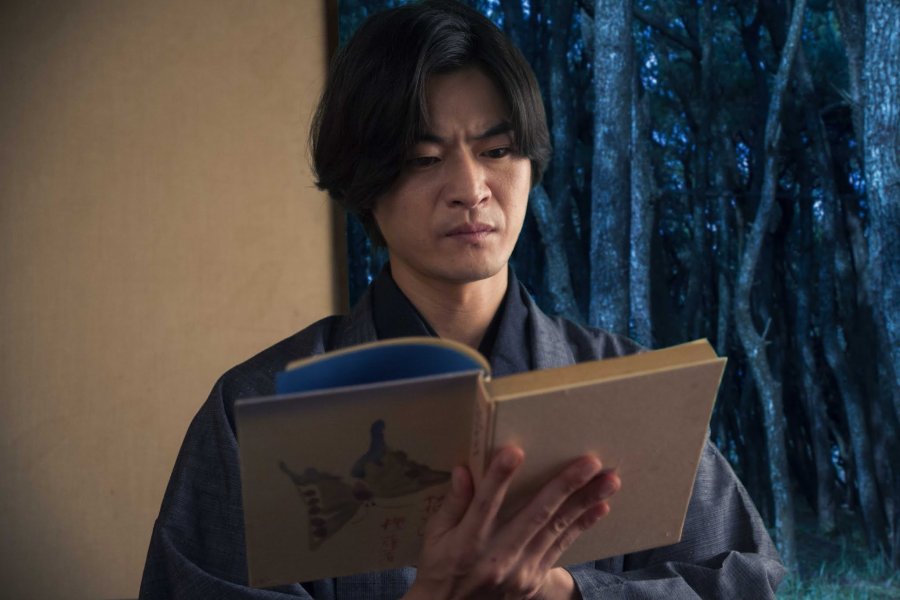

In 1988 came The Discarnates (a.k.a. Summer Among the Zombies), a melancholic tale about a screenwriter (Morio Kazama) who encounters his parents (Kumiko Akiyoshi, Tsurutaro Kataoka) who have been dead for years. This is Obayashi’s hot take on Dickens' Christmas Carol but within Japanese convention (respect for parents, plus horrible demons). Indeed, the main hero undergoes a sort of personal resurrection and tries to be a better person after surviving an extremely gruesome (Obayashi just does not let go), yet extremely cathartic finale. As in the case of Lonely Heart, Nobuhiko again dissects the themes of memories and longing while juxtaposing them with despair and tragedy through the lens of an adult.

The final movie released in the 1980s was Beijing Watermelon (1989), a slice-of-life drama inspired by true events revolving around a grocery store owner (Bengal) who helps poor Chinese students in Japan. This is nearly Ozu-style cinema, a completely unusual field of work for Obayashi, yet he manages to make it so peaceful and touching. There is no need for larger-than-life phantasmagorical visuals because the reality itself is impactful enough. What is more, the meta ending gently alludes to the Tiananmen Square protests and massacre.

The 1990s |

Nobuhiko stepped into a new decade with the documentary Making of Dreams: A Movie Conversation Between Akira Kurosawa and Nobuhiko Obayashi (1990). In this 150-minute-long odyssey, the viewers take a look at behind-the-scenes footage and interviews with the cast and crew while Kurosawa was shooting his penultimate picture. Additionally, there are also discussions between Kurosawa and Nobuhiko himself on a variety of topics concerning cinema. “Our age gap was like that of father and son and he treated me well,” said Obayashi (source) and added that Kurosawa left a message to all future filmmakers around the world. That is to say, Kurosawa hoped that the power of cinema could build a peaceful world in 400 years. Therefore, making movies warning about the war is a generational struggle and it is up to Obayashi and other filmmakers to pick up the mantle left by Kurosawa (source).

Obayashi returned to feature films in 1991 with Chizuko’s Younger Sister. In my opinion, he goes into hardcore melodrama mode in this one. It is a tale of grief and loss with nuanced performances of Ishida Hikari and Ittoku Kishibe accompanied by powerful music composed by Joe Hisaishi. Nevertheless, this is not a cheerful romance story nor a horror ghost tale. To be honest, the film is tonally inconsistent and has some really questionable moments (brutal death sequence, attempted rape scene, extramarital affair). In consequence, it does not hit the same mark as the previous Onomichi-based movies.

|  |

In 1992, Obayashi turned to making a coming-of-age comedy with a touch of rock and roll. The Rocking Horsemen focuses on a high school student (Yasufumi Hayashi) in the 1960s, who becomes mesmerised by the sound of the “Pipeline” song by the Ventures. Consequently, he proceeds to recruit his friends, gathers equipment, and set up a rock band. The movie’s positive vibes and witty dialogue precede Swing Girls (2004) and Fish Story (2009). Keep an eye for the supporting part done by super young Tadanobu Asano!

1993 saw the premiere of Samurai Kids, one of the most commercially successful Obayashi’s movies. This film is a true embodiment of the magic of cinema. Obayashi redeems himself in the family adventure genre after The Drifting Classroom with this extremely heart-warming tale about a child who forges a friendship with a tiny samurai. Needless to say, there are lots of crazy adventures along the way and a wonderful finale that will make you tear up. Tsutomu Yamazaki is amazing as a samurai! Added bonuses are Joe Hisaishi’s amazing music score, Ittoku Kishibe and Jun Fubuki as the kind-hearted parents, and a gorgeously cute cat called Hosuke!

That same year, Obayashi released a three-hour-long drama Haruka, Nostalgia which has a similar tone to Chizuko’s Younger Sister and again features Hikari Ishida in the leading role. Still again, this is very much indeed an idiosyncratic tale about the complex meta-relation between reality and fiction. Yet, I found it difficult to buy into the romance theme because of the age difference.

|  |

Goodbye for Tomorrow (1995) is a pleasant surprise after Chizuko’s Younger Sister and Haruka, Nostalgia because it evaluates sentimentality and overcoming loss in a more personal manner. Adapted from Jiro Akagawa’s novel “Forgotten Things at Midnight,” the story focuses on people who receive mysterious messages from loved ones who were killed 3 months earlier in a shipwreck. It is about being able to say goodbye and in this regard, the movie very much reminded me of Luc Besson’s Le Grand Bleu (1988) and Krzysztof Kieślowski's Red (1994).

Sada (1998) is the third movie based on the true story of a geisha who murdered her lover after A Woman Called Sada Abe (1975) and In the Realm of Senses (1976). In contrast to previous cinematic retellings, Obayashi does not go full NSFW but provides the most “mainstream” (source: Sharp) perspective on the life of the elusive prostitute. With the brilliant leading role of Hitomi Kuroki, Sada becomes an unnerving and at times phantasmagorical tale that humanises the brutal act committed by the heroine.

The 2000s |

The decade of the 2000s proved to be the least creatively potent for the filmmaker because he managed to release only six motion pictures. Interestingly, these are also the hardest to come by movies out of Nobuhiko Obayashi’s filmography. I have only managed to track down The Reason (2004) and Switching - Goodbye Me (2007). The first movie is a very demanding crime drama in which the director basically deconstructs the popular genre by attempting to tackle the difficult question: What makes people commit murder? Switching - Goodbye Me, on the other hand, is a remake of Exchange Students (1982), but this update did not win me over. In 2008, Obayashi made a slice-of-life drama titled Scenery to Remember which marked his final motion picture of the decade. He would not make another movie for four years. Perhaps this was caused by the untimely death of one of Obayashi’s frequent collaborators, Toru Minegishi, who appeared in his films since The Visitor in the Eye (1977) (source).

The Anti-War Trilogy (2012-2017) |

“I am not making anti-war films. I just do not like war,” stated Obayashi in an interview (source). Having been inspired by the message of the aforementioned Akira Kurosawa, the director set out to make a personal trilogy evaluating the complicated relationship of the Japanese with World War II and also serving as a direct response to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake: “For those who experienced losing the war, 3/11 was a do-over. I thought that no longer will the Japanese think materialistically or conveniently. I thought we will learn to be compassionate and work together. I thought we were going to be okay and so I made Casting Blossoms to the Sky and three years later, Seven Weeks. I thought the Japanese will cast away nuclear power plants and will move in a better direction, but sadly the government doesn’t move that way. And the one reason is that without war, they can’t feed themselves. It’s the military-industrial complex. So, of course, the government won’t stop a war” (source).

Casting Blossoms to the Sky from 2012 feels like a time capsule of testimonies made by people who experienced the atrocities of war in Nagaoka in 1945. We follow journalist Reiko Endo (Yasuko Matsuyuki) as she explores the city and collects memories of its residents. Some lost loved ones in the course of air raids, whereas others were badly injured. We learn that mock-ups of the atomic bombs were dropped on Nagaoka because the Americans were already practising before obliterating Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Obayashi condemns the futility of war in a series of striking visuals which constitute a stage play prepared by the people of Nagaoka. The movie concludes with a real Nagaoka Fireworks Display in memory of victims of the Pearl Harbor attacks and of the US air raids.

|  |

Interestingly, Seven Weeks (2014) takes the theme of reconciliation and nostalgia to another level. The main protagonist of the film is Doctor Mitsuo Suzuki (Toru Shinagawa) who passes away at the age of 92 in the town of Ashibetsu. His sister (Tokie Hidari), grandchildren (Saki Terashima, Takehiro Murata, Yutaka Matsushige), great-granddaughter (Hirona Yamazaki), and former employee (Takako Tokiwa) gather together to perform mourning ceremonies. However, not everything goes according to plan. What exactly were the circumstances of Suzuki's death? It is up to the relatives to discover the traumatic past of young Suzuki who was fighting the Russians in Sakhalin, back when it was still under Japanese jurisdiction. Although the war ended in August 1945, the surrender order did not reach Sakhalin until September 5. For Mitsuo, other soldiers, nurses, and residents of Sakhalin, this is the real date when the war ended.

In Seven Weeks, Obayashi takes great advantage of flashbacks, shifting narratives, and visuals reminiscing magical realism. In consequence, this is not just a story about atoning for past sins, but also about the possibility of reincarnation. Where do we come from and where are we going? Obayashi answers these questions by stating that behind each death there is a new birth. Something has to end so something new could begin. Life is a journey that has to be cherished rather than wasted on unnecessary suffering.

Last but not least, Hanagatami (2017) can be regarded as Obayashi’s anti-war magnum opus. Inspired by Kazuo Dan’s novel, the director was developing the project for 40 years, and when he finally got the budget to make it, he was diagnosed with lung cancer. However, this did not stop him from shooting the film. In His Promise documentary, we can see frail Obayashi, supported by his wife Kyoko, relentlessly giving instructions to the cast via walkie-talkie.

|  |

Originally, the screenplay of Hanagatami was Obayashi’s original pitch to Toho back in the 1970s, but the executives said they wanted a shark movie (source). “I wanted to make it 40 years ago but nobody cared about it,” said Obayashi in an interview and added a surprising remark: “The script for Hausu and Hanagatami are actually the same. Takako Tokiwa’s role is called Keiko Ema. In Hausu, the new stepmother was called Ryoko Ema. They’re the same” (source). Obayashi’s statement may be somewhat ambiguous because the two movies tell radically different stories, but essentially, both pictures focus on the destruction of innocence in the face of brutal reality.

Hanagatami itself can be best described as a performance art caught on camera. Nobuhiko explains that he did not do any rehearsal with the actors and actresses in order to capture their genuine reactions and expressions. What is more, the way Hanagatami was shot is also interesting. To compensate for his small budget, Obayashi breaks nearly every filmmaking convention and, as a result, we get CGI landscapes, artificial camera pans, rapid zoom-ins, and mirrored angles of certain shots. Consequently, the director creates “a strange mixture of excitement and melancholy” (source).

Hanagatami is not a motion picture but rather a visual poem that pulls you in with its rawness and wickedness. This is Obayashi’s harsh statement against the foolishness of youth. In the film, we follow Toshihiko Sakakiyama (Shunsuke Kubozuka) who attends a school in Karatsu and frequently encounters his colleagues (Shinnosuke Mitsushima, Keishi Nagatsuka, Tokio Emoto) as well as his aunt Keiko (Takako Tokiwa) and ailing cousin Mina (Honoka Yahagi). On the day when Pearl Harbor is attacked, Toshihiko can’t help but celebrate. However, this is also the day that marks the death of Mina. Together with her death, all of the other characters lose their innocence in the face of the upcoming war with America. “I’ll survive in the red, setting sun of Manjuria,” Keiko repeats the words of her dying husband as if foolishly believing in the success of the Japanese East Asian Order. During an English class, Toshihiko asks his nihilistic friend Kira: “What will happen if Japan goes to war with the country of Edgar Allan Poe? We won’t be able to read Black Cat anymore.” Obayashi answers that only death awaits all the young men who go to war. Toshihiko has the luck of being one of the few soldiers who survived the traumatic period, but at what cost? As an elderly man, does he fear death? Does Nobuhiko Obayashi himself fear death? In the chilling final scene of the film, the actor playing Toshihiko appears actually as Nobuhiko and ponders on this troubling issue…

Labyrinth of Cinema (2019) |

After completing Hanagatami, Obayashi joked that “it would have been prettier if he died right after completing the movie so that people could say that he lived out his 40 year-long dream” (source). Well, call it heavenly grace or serendipity but Nobuhiko had enough strength to bid us farewell in his final movie called Labyrinth of Cinema.

In my opinion, Labyrinth of Cinema is the most definite Obayashi movie, which cannot be described with words. It has to be seen to be believed. Similarly to Hanagatami, it is another “colourful antiwar fantasy,” (source) but more light-hearted in tone than its predecessor. Nobuhiko once again grapples with the themes of the futility of war and the bombing of Hiroshima, yet he also expresses his love for movies through numerous references and his auteur style of filmmaking.

In the final scene, we see Obayashi himself playing the piano and addressing the audience: “Before ‘The End’ let me interrupt the movie with a song. I hope you will enjoy it". The song is a piece composed by Toriro Miki and sung by Tetsuya Takeda, and it is followed by a subsequent message from Obayashi in which he warns viewers about contemporary “seeds of brutality”. This resonates deeply, especially in the context of the 2022 events.

Trivia |

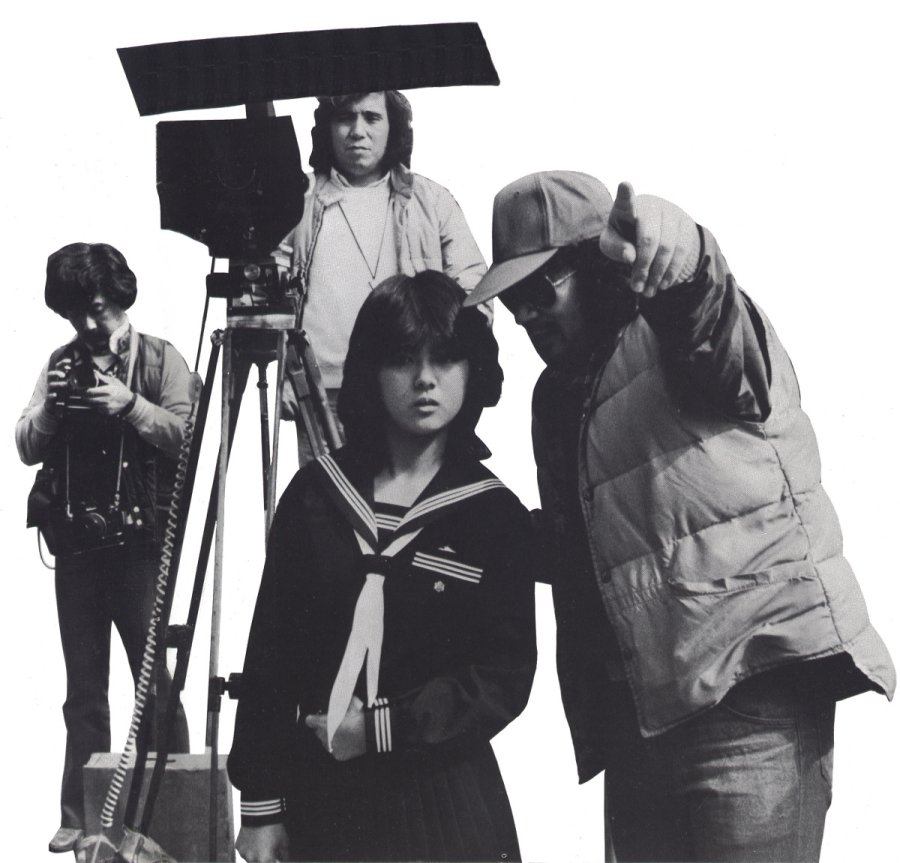

Behind the scenes photos from House (top) and School in the Crosshairs (bottom). |

|

It is the end of this ultra fan’s guide. Thank you for bearing with me up to this point. For the past month, I have been relentlessly watching, reading and researching the topic of Nobuhiko Obayashi. Exploring his films was indeed a dreamlike voyage bursting with energy, passion, sentimentality, romance, and a few scares along the way. While writing this lengthy article, I constantly asked myself the following: How come Nobuhiko Obayashi is still not popular in the West? It would be safe to assume that the premiere of House on physical media would usher in other Nobuhiko’s movies to the European and American markets, but these are still predominantly present at film festivals or special retrospectives. I think that in the times of mainstream mediocrity and cultural enchantment with anything that is depressing or politically charged, the Occidental sphere very much needs vibrant, dynamic, and wonderfully insane movies by Nobuhiko Obayashi.

All things considered, he was a visionary who not only mastered the language of the film but who constantly sought to redefine it. Allow me to end this article with the director’s own words:

For me ‘freedom’ is doing something that no one has done before. To do something no one else has done before… is important. For us filmmakers it’s the most important thing of all. Some say that because movies have a long history and everyone all over the world has been making them everything has been done already. There’s nothing more to do. I say that’s nonsense. There are still a lot of things that have never been done. (source)

The Author’s Endnote: For the purposes of this article, I have tried to watch the works of Nobuhiko Obayashi as legally as possible. My thanks go to a kind soul from South Korea who was willing to share some of the titles which are to date unavailable in the West. Evidently, I also encourage the readers to check out the movies fair and square. House is available on numerous streaming platforms. Sada is available on The Criterion Channel. The Anti-War Trilogy is out on Blu-ray from Third Window Films (also on Arrow Player), and this distribution label is going to release School in the Crosshairs, The Little Girl Who Conquered Time, The Island Closest to Heaven, and His Motorbike, Her Island in Fall this year. Labyrinth of Cinema is available online on Amazon Prime Video and on the beautiful Blu-ray edition from Crescendo House.

Images used: Wikipedia (feature image) * ScreenAnarchy (top image) * Twitter (Nobuhiko and Kyoko- 1968) * Austin Film Society (Nobuhiko and Kirk Douglas) * The Globe and Mail (House photo) * Ob's House Blog (Behind the scenes photos) * DayDayNews (Concluding photo) * ScifiJapan (Nobuhiko and Chigumi- 2015) * The Japan Times (Hanagatami photo) * Remaining photos are screenshots taken from the movies *

Sources: Kawaii Magazine No. 5/2019 (pages: 86-88) * A Critical Handbook of Japanese Film Directors: From the Silent Era to the Present Day by Alexander Jacoby and Donald Richie * Behind the Pink Curtain: The Complete History of Japanese Sex Cinema by Jasper Sharp * Obayashi, Nobuhiko: Senses of Cinema * Wikipedia * Nobuhiko Obayashi, Vagabond of Time * Obayashi Nobuhiko, a Movie Man * Obayashi Nobuhiko’s Once Seen Movie Theater * ‘Labyrinth of Cinema’: Nobuhiko Obayashi’s final film is a colorful antiwar fantasy * For filmmaker Nobuhiko Obayashi, freedom was the most important thing of all * Nobuhiko Obayashi: A life spent working among Japan's movie greats * 'Hanagatami': Extravagance on the edge of war * Filmmaker Nobuhiko Obayashi devotes himself to a message of peace via the big screen * AKB48 and director Nobuhiko Obayashi honor postquake efforts in Tohoku * The Cine-Files: Nobuhiko Obayashi’s 1977 horror film ‘House’ * Fantasia 2018: Nobuhiko Obayashi and the Perpetual Promise of Youth * Nobuhiko Obayashi conveys the great filmmaker Akira Kurosawa’s last message and entrusts world peace to future filmmakers * 'Hausu' is beyond strange * House: The Housemaidens * Beyond House: Nobuhiko Obayashi * Ob's House Blog * The Forgotten: Nobuhiko Obayashi's "Emotion" (1967) * Working for Tomorrow: An Interview with Nobuhiko Obayashi * Nobuhiko Obayashi explains the limitations of the culture industry * The Legacy of ‘House’ Director Nobuhiko Obayashi – Your Japanese Film Insight #9 * The Sky Is Always Blue: Exploring Nobuhiko Obayashi’s Anti-War Trilogy * House - Q&A with Director Nobuhiko Obayashi * HOUSE (HAUSU, 1977) - Constructing a Psychedelic Haunted House Horror Film (Behind the Scenes) * Nobuhiko Obayashi Commercials * An Interview with Nobuhiko Obayashi * Interview with Arthur Johnson - Actor in Nobuhiko Obayashi's Drifting Classroom * Nobuhiko Obayashi's Movie Trailers *

Ebisuno92’s Previous Articles: * Pitching Ghostbusters as a J-Drama * A Tribute to Sonny Chiba (with Old_Anime_Lady) * If The Woman Behind The Counter was a J-Drama * Underground Nightmares and Social Anxieties: Aum Shinrikyo on Film * For Comrade's Eyes Only: Interview with Johannes Schönherr (with Seonsaeng) * Takeshi Kitano Is Gearing Up to Direct His Final Film "Kubi" * From Zero to Hero: A Retrospective Guide to Yaguchi Shinobu (with Joe Shiren) * An Ultra Fan's Guide to Takeshi Kitano * An Ultra Fan's Guide to Kyoko Kagawa * Feel the Power of Office Ladies: Shomuni Retrospective * "Watashi, Shippai Shinai No De!”: Daimon Michiko as the Ultimate Doctor-Hero (with Reika Bleu) * "Come on over, Spiritual Phenomena!” TRICK, A Franchise Retrospective * From Best Korea with Love: An Introduction to North Korean Dramas & Movies (with Seonsaeng) * Cursed Cassettes, Countdowns, and Corpses: A SFW Guide to the Ring Series * Blast from the Past: Did Bayside Shakedown Destroy Japanese Cinema? * Weekend Recommendations: Father Knows Best * Godzilla's on the Loose: 65 Years of Kaiju Rampage * An Ultra Fan’s Guide to Yeoh Michelle * Blast from the Past: A Guide to “Girls with Guns” Genre * Weekend Recommendations: Old School Movies * Ebisuno92's Weekend Movie Picks *

Thank you for reading.

Big thanks to the editors for their hard work.

Edited by: YW (1st editor)