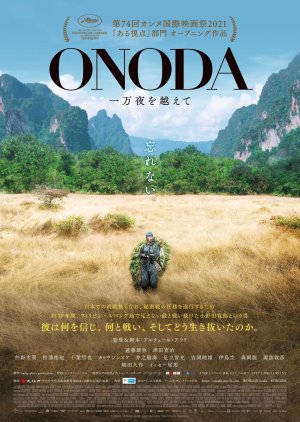

"Whatever happens, we'll come back for you"

Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle told the true story of one of the last Japanese holdouts after WWII. Japan surrendered on September 2, 1945. The war ended for Onoda Hiroo 29 years later on March 9, 1974. During his training as an intelligence officer he was told he had to survive at all costs and that "Whatever happens, we'll come back for you.” Onoda learned the hard way that the military was not as loyal to him as he was to the mission.“We will be back for you. We will be back. Whatever happens---survive!”

Late in WWII, Onoda Hiroo fails pilot school because he has a fear of heights and dying. He’s recruited to train as an intelligence officer and in guerilla warfare in December 1944. Before he leaves, his father (mother IRL) gives him a dagger to kill himself with rather than be captured should the need arise. When he arrives on Lubang Island none of the other officers will help him with his mission which was to disable the airstrip and port. Most of the soldiers are hungry, demoralized, and/or ill. The Americans take the island shortly after his arrival. Soon the only Japanese soldiers not dead or captured are Onoda and the three men he chose to work with him---Kozuka, Shimada, and Akatsu. Believing they must hold their ground until more Japanese forces arrive, they set up camp in the jungle and cause damage to the farmers’ fields in order to keep the locals afraid of them. They subsist on whatever they can find or steal, taking up residence in caves or homemade huts. The small group of holdouts refuse to believe the war is over and patiently wait for reinforcements.

“Try to change the way you see things”

Two different actors played Onoda and his second in command, Kozuka. They all performed admirably as the characters aged and learned to survive in the jungle and rely on each other. The film confined most of the shots to the men and their duties which displayed their arduous methods of staying alive. Bound by their limited outside contact, their lives seemed incredibly sad. They were completely isolated and separated from family and loved ones. As much as the film focused on the holdouts it would have been nice to gain the locals’ perspective of the killers in the hills and the fear they instilled for a time.

“They know that what is complicated and even incomprehensible, sounds true!”

My first thought when Onoda’s father handed him the dagger and told him, “Your body is the Fatherland. Do not let it fall into enemy hands,” was the Spartan mothers’ declaration to their sons, “With your shield or on it.” Ordered not to die and trained to unconditionally obey orders, unwilling to return home defeated, and determined to prove himself, Onoda’s psyche was trapped in a nightmare in the jungle of Lubang. The outside world and even loved ones attempted to convince Onoda that the war was over, but he could only see conspiracy theories everywhere he looked, convinced that Japan was still fighting. Eventually, he had access to newspapers, magazines, and a transistor radio but believed it was all an elaborate ruse to trick them. At some point, Onoda’s rigid obedience and views appeared to come across as an over-inflated sense of self. Why would the enemy go to such extraordinary lengths to trick one man? If he was that important they could have sent in a wave of soldiers to kill him or just bombed the jungle. Onoda had a high level of cognitive dissonance as he clung to his beliefs in the face of harsh opposing facts.

“What if we killed people we’re no longer at war with?”

Onoda and his men were resourceful and resilient. The youngest left after nearly 5 years and another was killed after almost nine. When the second in command was killed after 27 years of holding out, it seemed to chip away at Onoda’s confidence. Despite their incorrect assessments, Onoda and his men were a product of their training and propaganda. They truly believed they were serving the greater good by holding their position on the island. It took as much determination as denial to be separated from family and friends, to live on roots and fruit often with only rudimentary shelter for nearly three decades. In 1974 a Japanese adventurer discovered Onoda and befriended him. The young man caused Onoda an existential crisis as the holdout could no longer deny that Japan and the world had changed. The military bore responsibility as well. The loyal soldiers killed 30 inhabitants over the years. Two of the four died pointlessly and Onoda lost 30 years of his life because no one cleaned up the mess they created. These soldiers were imbedded on islands in the last months of the war when the writing was on the wall. VE Day occurred not long after Onoda was stationed on Lubang and Japan surrendered in August of 1945. All it took was for Onoda’s superior to come back for him. Unfortunately, for Onoda, his men and the people of Lubang, it took nearly 30 years to do so.

30 April 2024

Esta resenha foi útil para você?

Romanticisation at a cruel cost

The credits roll and my first thought is: What is the Filipino take on all this?But we’ll get to that shortly.

The film Onoda is the fictionalised story of Hiroo Onoda, one of the last Japanese soldiers to surrender after the end of WWII. He was a ‘holdout’ on the Filipino island of Lubang until 1974. He survives in the jungle in denial of the war's end, losing his compatriots one by one. The story is fictionalised in more ways than one, but we’ll get to that shortly too.

At face value, the movie is surprisingly engaging given its long run time. There are also some pretty landscape shots. But that’s about all the positives I have for this piece of cinema. Buckle yourself in, folks!

Let’s start with a simple point. For a story so embedded in its Filipino geography, the decision to shoot in Cambodia feels off. And there’s good reason.

It’s a European production…with a French director…about a Japanese soldier…in the Philippines. Yes, that should raise an eyebrow.

“If you add up all those nationalities [who worked on the film], it makes the film from nowhere,” director Arthur Harari says in an interview with Asian Movie Pulse.

Yet, Cambodia was the destination of choice because Harari wanted a French-speaking film crew. Cambodia is a former French colony. It's certainly not “nowhere”. Neither is Lubang. The shoot location is only one of the ways in which colonial politics seeps into this cinematic production.

Many a filmmaker has simped for the romantic man-survives-jungle trope and Harari is no different, citing the likes of Joseph Conrad as original inspo for this movie. But it comes at cruel cost to the Filipino characters and their real-life counterparts.

I agree with James Lattimer’s assessment that the Filipino characters are used as “little more than cannon fodder”. Harari’s avoidance of the Filipino side – in terms of both geography and narrative – is a result of wilful ignorance. That is because he relies on Onoda the myth, not Onoda the man.

In true à la française style, Harari projects some kind of universalist reading of human experience onto Onoda’s story.

“I didn’t read historical books about Japan or the war,” he admits in an interview, “because the fact is that everything about Onoda’s story can be understood even if you don’t really know the general situation of the war, the Pacific War, or the history of Japan.”

In fact, Harari only read one book about Onoda, written by two Frenchmen: ‘Onoda: Seul en guerre dans la jungle’. As far as I can tell, the text seems sympathetic to Onoda’s side of the story, describing Onoda as a “prisoner of that island, of that oppressive jungle” (own translation). Heart of Darkness much? Either way, Harari mostly upholds the romantic hero image of Onoda in the film, an image which Onoda himself first established when he published his autobiography.

But even a little bit of reading about Japan or the war reveals how the Filipino people were cruelly caught in colonial crossfire. Their lives and land were used as military props and staging by the Japanese (and, of course, the Spanish and the Americans before that).

Onoda’s autobiography omits Onoda’s many gruesome murders of Lubang’s residents. Tsuda Shin, ghost-writer of Onoda’s autobiography, revealed this much when he wrote his own exposé on Onoda a couple of years after the autobiography came out.

Even now, it’s Harari’s cinematic project that receives the funding and the spotlight. Meanwhile, the Filipino side of the story struggles to see the light of day. Mia Stewart has set out to correct the record via documentary making. Her maternal relatives lived – and still live – in Lubang and experienced first-hand Onoda’s violent atrocities.

“They weren't just shootings, there were very violent killings that involved beheadings and mutilating bodies,” Stewart says in an interview with SBS.

Lack of funding means her documentary still hasn’t been released. But it’s a good cause. A myth like Onoda’s needs interrogation.

“We will never really know if Onoda knew the war was over or not. Regardless, he killed civilians. While I can't undo those deaths, I can change how we tell the story,” Stewart says.

----------

Stewart’s forthcoming documentary, ‘Searching for Onoda’: https://searchforonoda.com/

Stewart’s interview with SBS: https://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/mias-uncle-bled-to-death-she-wants-to-set-the-record-straight-about-why/qig3whkdb

Insights on Harari’s approach come from this excellent A. E Hart piece: https://www.documentary.org/online-feature/domitable-myth-three-depictions-japanese-holdout-soldier-hiroo-onoda

James Lattimer’s review: https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/reviews/onoda-10000-nights-jungle-lost-filipino-wilds

Esta resenha foi útil para você?